Olu Oguibes Finding a Place Nigerian Artists in the Contemporary Art World

The Practice + Theory series is sponsored in part by the Frances Dittmer Family Foundation.

Ethnographia 2.0, 1997–99, multimedia installation. Photo by Castello di Rivoli, Torino. A multimedia version of theEthnographia serial featuring a display of selected literature and an interactive CD-ROM.

The world is a small place, it seems, and people move in and out of our lives in unexpected ways. And then it has been with Olu Oguibe, an artist, writer, theorist and curator—also as, I was presently to acquire, a musician and poet. He is part of the contempo generation of African-born artists who emerged on the international scene in the early '90s. I first met him years ago, when he delivered a talk at New York Academy that focused on the dual topics of international exhibitions—he had just curated one in Nippon—and globalization. At that time he was a booster for the new international culture that he believed was emerging and, tangentially, the Internet. On that occasion we exchanged our very dissimilar views on the nature of cultural imperialism. What most impressed me was his view that any insistence on 3rd world people defending their national cultures against Westernization and modernization was based on a romantic vision that would restrict their entry into the modernistic world. Sitting in his Brooklyn studio as he was preparing his bookThe Culture Game, a drove of disquisitional essays, notes and interviews from the terminal decade (just out from the Academy of Minnesota Press), we pigeon into a cyclone discussion of his past, our nowadays and the always-irresolute nature of contemporary fine art, identity, culture and politics.

Saul Ostrow You're a Renaissance man whose interests range from pop culture to engineering science to painting and installation to postcolonial theory. You are Nigerian born, English educated and living in the States; you are an artist, a theorist and a curator, and yous make work that can only exist described as international. How did yous come up to occupy this position?

Olu Oguibe This was always a difficult question for me, and I haven't always felt about it as I do now. In the mid-'90s I wrote an essay called "Imaginary Homes, Imagined Geographies," in which I dealt with questions of identity and belonging, and my position at the time was to challenge the fastidious attachment that we develop with the idea of dwelling house, tying dwelling house to where nosotros were born. I was coming from what some would depict as an Igbo betoken of view. I am Igbo, and the Igbo are a traveling, mercantile people. We have a maxim: "Where the centipede dies is its grave." Another is "You lot mend the roof over the firm that you alive in." That is to say, home is where the "hearth" is. Merely the Igbo also take another, complex proverb, "Agaracha must come back."Agaracha ways "after all travels," so, no matter how far you travel, you must return somewhen. I recently had a discussion with a friend, a Nigerian poet living in Germany, and he described himself every bit "cosmopolitan," distancing himself from his Igbo identity. I said, "You know, it's all very well to see oneself equally cosmopolitan, merely I'm beginning to experience that I was wrong to take rejected the idea of a homeland. I'yard beginning to notice something inherently logical about ideas of dwelling, especially if you are in a state of affairs that reminds you of your outsiderness, your otherness." It makes sense to secure an identity and not simply live in that "other" world of want.

And so You and I once had an exchange at NYU nigh exactly this indicate. You said and so that for you, to effort to secure an African identity would exist to reassert a Western notion of who y'all should be.

OO I still hold fast to that. That'south the great irony, that fifty-fifty every bit I reject that particular effort, I feel a personal compulsion to identify with something smaller than that. You might say that the whole exercise hinges on a sense of insecurity.

And then Looking at it in terms of marginalization, I'd say destabilization rather than insecurity.

OO Destabilization is probably the term I'm looking for. Merely politically speaking, in that location is insecurity as well. There's something very physical about information technology, in that I could go sent back to Nigeria tomorrow. And the irony goes on forever: that aforementioned thing that is reassuring to me would victimize me in the Nigerian context. For a long time Nigeria excluded the Igbo from national politics, basically treating the states as second class. Information technology began as a punishment for our seeking self-determination in Biafra, but now it'southward the culture.

And then So it'due south the real politic versus how we theorize it.

OO Exactly. Otherwise, my story is straightforward. I was built-in in Aba, a commercial city in Eastern Nigeria, only because of the Biafra war my family unit returned to the boondocks where my parents were built-in. On the family tree, everyone right up to my father was a deity priest. However, my grandfather did the sacrifices necessary to free his son of any obligation to the priesthood. Ironically my father notwithstanding ended up as a Christian evangelist. He had a burning want to come up to America to written report, an ambition that was sabotaged by the war. Then, very early in my upbringing he projected that onto me, in terms of how ambitious I must be. My father's library was all Christian religious books and European history. I would go through all this religious literature and discover pictures of Christian colleges across America and I'd think, I've got to become there. I always imagined myself as part of a much larger world than our tiny town, which had no electricity or running water. My transistor radio was ever tuned into Radio Beijing, the Voice of America, Radio Moscow. The BBC was a given, too; everyone listened to the BBC. That and reading were my means of escape into the world. As a kid I wanted to be a journalist, in fact, a media tycoon. I was going to found my own magazine.

SO At what bespeak did yous start to question your vision of the cosmopolitan you?

OO Oh, much later. I felt a scrap like Lemuel Gulliver, who experienced the whole world and became a different person from the provincial English man of his time. What I forgot was that Gulliver went back only no 1 would believe his stories. They tried to pry him away from all that feel of the universe. Reading Swift, I latched on to how provincialism violently opposes exposure but I missed the point, which is that fifty-fifty though Gulliver could accept lived in those fantastical places he went to, he still returned to England—if only to help reshape people's vision of the world, their sense of reality. But I don't think y'all can fully return.

SO You can't go home again. Or, at least, the same person doesn't go home.

OO And the identify you find upon your render is non the same. Everything has changed in the interim.

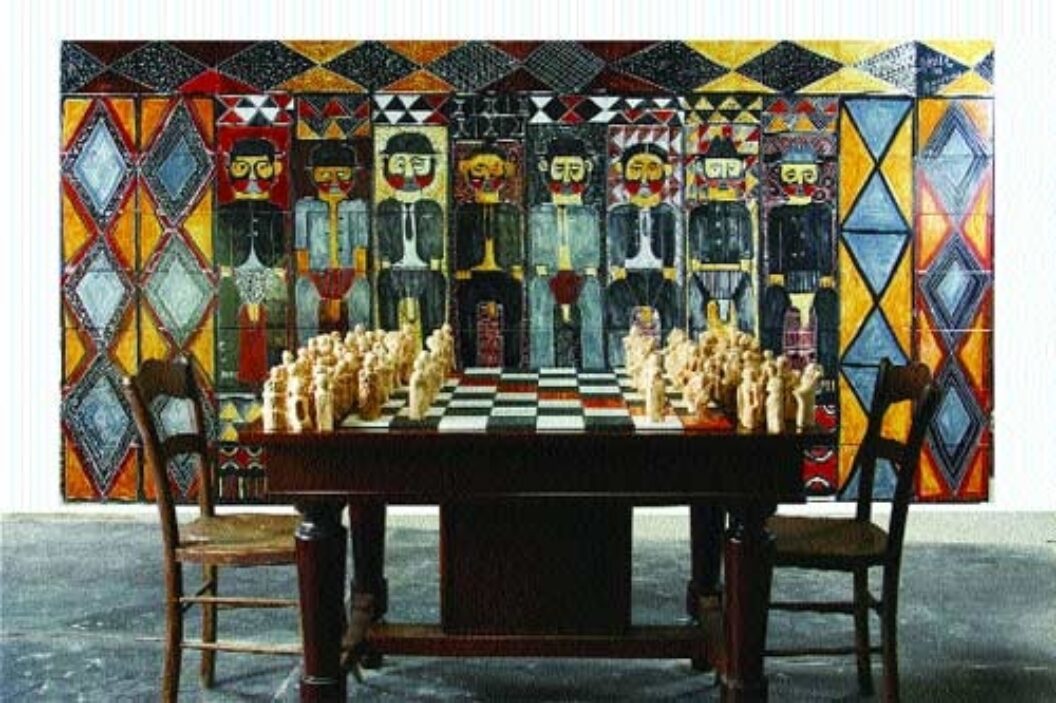

Game, 2003, ceramic installation, xiii × 6½ × 15 feet. Lucio Fontana studio, Albisola Marina, Italy. A ceramic mural with 8 figures and a game set with 101 terra-cotta figures.

So So you wanted to be a journalist. How did you lot come up to art?

OO That was easy: my father was an artist. While he worked in the ministry after the state of war he too made wooden statuettes, religious icons for Catholics, every bit well equally carved masks for masking societies, although he belonged to a religious sect that shunned both practices. (laughter) I helped in the workshop, sanding and painting, making my own little figures for homework, and I did fine arts in high school. I somewhen studied art at the Academy of Nigeria.

And so What was your access to what was going on in the kickoff earth in terms of black consciousness? For instance, that the Black Arts Move in London was very of import.

OO My first knowledge of the Black Arts Movement in Uk, which was quite unlike from the African American movement, was circuitous. However, with regard to African American art, nosotros had access toBlack Arts Mag, now theInternational Review of African American Art, and at that place were publications that came through the local USIA [U.s. Information Agency] office. Some professors had journal subscriptions. Of grade in one case you realize at that place's something happening out there, you make the effort to find out what information technology is. I was more familiar with the scene in America, having minored in African American art at both undergraduate and graduate levels.

SO Were Nigerian artists going back and forth between London and New York? Was at that place a quote-unquote art world in Nigeria?

OO Yeah. That was another crucial aspect of my education: some of these individuals did go back and forth. The sculptor El Anatsui was exhibiting around the world, including United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and the US. So was my painting professor, Obiora Udechukwu, who also studied Chinese painting. But you still had people on the Nigerian fine art scene who were entrenched in the belatedly colonial flow, including young people who simply made still-life and landscape paintings. At that place were likewise leftovers from the early postcolonial menstruum, the early on nationalist period, when Nigerian artists had not quite deciphered how best to correspond a postcolonial reality and were still engaged in forms and styles very closely aligned to the international Negritude move. They were making images of masks and so on. Just you had artists who were far more sophisticated in what they were exploring every bit individual artists, not merely every bit part of whatever nationalist cultural move.

SO Is that the general condition in Africa, regardless of whether the colonial past is English language, French or Belgian?

OO There was something happening in Nigeria that was probably not happening in other places beyond the continent, and that hinged on a core group of people, including those fellows I just mentioned.

SO I'yard leading upward to the question of why you left.

OO I know. (laughter) I don't know if my experience is typical. It had less to do with art than with my personal circumstances. Frankly, I was heartbroken to leave. My story and then got repeated with other people because it was political. I went through a long period of political victimization that sometimes manifested itself academically.

And so Does this have to do with being Igbo?

OO It was more national. Nosotros had a series of military dictatorships and I was pro-democracy. Regarding my personal cultural location at that point, and in terms of my journey of self-discovery, it was detrimental to leave Nigeria. But one of my professors was approached by the British Council to advise people for the British Foreign and Commonwealth Role fellowship, which is Great britain's virtually prestigious fellowship for foreigners. He suggested that a bunch of the states go in for interviews. I was offered a place at the University of London to do my PhD. Then information technology was—

SO Chance.

OO Chance. (laughter) We all had the aforementioned plan in that era: you make it in the West intent on returning abode the day you lot finish your plan. But the closer we got to going back, the more than people from domicile would write and say, Don't bother coming back, what are you lot coming back to?

SO Was that because of the political situation?

OO The political situation, the economic system—everything seemed to take collapsed. People at home felt that you were safer away. In my instance, a couple of weeks afterwards I arrived in London I received a letter of the alphabet from a close friend, Ike Achebe, son of the novelist, informing me that there was a nationwide warrant for my arrest for political reasons. So, though I left voluntarily, all of a sudden I became a avoiding. It would be several years before I could render or move freely within the country. Many of us had to leave for economic reasons, and quite a few for political reasons. Very few of u.s. left only to explore the world. In Nigeria, artists tin make a fairly healthy living as artists. I sold more than piece of work in Nigeria than I have the whole time I've been abroad.

So In that way the Nigerian situation is closer to the Southward African state of affairs.

OO Although there aren't equally many commercial galleries in Nigeria. We but had very healthy relationships—which I would actually like to see more than of in the West today—between artists and patrons. People bought work considering they liked information technology or considering they wanted to support what you were doing, not because you lot were supposed to be the next large thing.

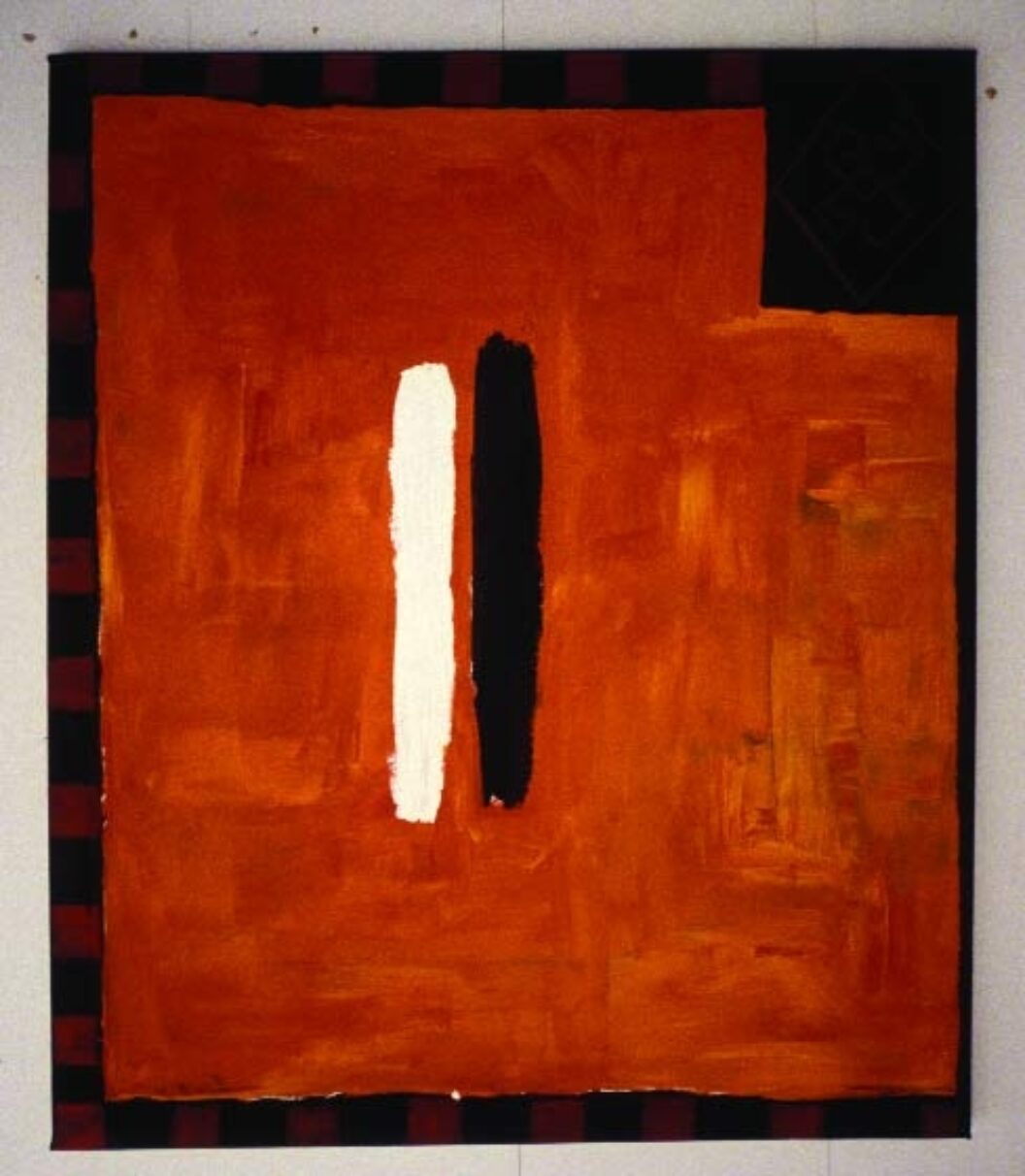

Lovers, 1993, acrylic on canvas, 71½ × 65¾ inches.Lovers is part of a group of 30 works defended to a afar Mexican muse for whom my last volume of poems was too written.

SO What was the civilisation you lot found in London?

OO What with my colonial training and my own prior exploration of that earth, at that place were few things I wasn't already familiar with, except I was quite depressed to arrive on the train and notice all that greenery. I wanted to see concrete; I wanted to see an industrial wasteland. To discover information technology so humanized was the culture stupor. (laughter) In terms of the culture itself, there was very picayune to shock. London has a huge African population, and so in a sense it was a familiar situation. I had some High german and English friends who eased me into their world, but in that location was always the African community to fall back on.

When I got there at the end of the '80s, the Black Arts Movement was changing. A practiced bargain of the development in that decade was made possible by an economic low, ironically, because it was the Thatcher era. Ken Livingstone, who is now mayor of London, was running the Greater London Quango, which spent a lot of coin on the arts. I believe that because of the riots and the political situation there was a certain liberal endeavor to support "black" efforts in Britain—"black" meaning everyone who isn't Caucasian. Supporting black cultural activity was a way to preoccupy young people, to reduce unemployment, to engage the population.

SO Was it likewise a form of cultural ghettoization?

OO That would reveal itself later. At that bespeak it was all enthusiasm—black artists were exhibiting, and some of them were quite nationalistic and wanted nothing to practise with the so-called mainstream. It wasn't long before the whole idea of center and periphery began to get knocked about. People were quite happy to take their own spaces, you know, blackness galleries, blackness cultural centers; it was all jolly. Past the time I arrived in '89, however, much of that back up had been withdrawn, and many of these centers were endmost down. The galleries folded because they hadn't figured out how to market black art.

SO The question was how to develop patronage.

OO Exactly. And by 1990 the Black Arts Move in United kingdom was pretty much over. Whatsoever hadn't been achieved by then would never exist achieved. People look at the scene today and think of Yinka Shonibare, Chris Ofili, Mona Hatoum; they remember that a lot of what was going on in the British fine art globe was positive. I am more hesitant to achieve that conclusion. What failed to happen is more significant than what ultimately did happen—the fact that very good artists like Keith Piper never found mainstream acceptance, for instance.

So Given your experience, practise you feel that all this was more than apparent to you as opposed to the people participating in information technology?

OO Information technology was crystal clear to me; I don't know if information technology had annihilation to practice with my extended outsiderness. At that place was already a shift away from that ideology of cocky-sustenance that was at the core of '80s cultural politics, and you could see the return of that perennial artists' desire to be part of the mainstream, peculiarly among young people who went to fine art school in London. Eddie Chambers and the residuum of the Black Arts Movement people had come from the provinces, and I remember that was very important. If they had studied in London, I am not sure they would take had the independence of idea to pursue what they pursued with such blowing and intensity, considering what Goldsmiths College teaches y'all is not to be a black artist but to be an artist who can succeed within the mainstream.

Then Intellectually, did Raymond Williams influence you once y'all got in that location?

OO Raymond Williams was office of the discourse, merely information technology was really more than David Bailey and Paul Gilroy, author ofThe Blackness Atlantic. In the early '90s the Birmingham School under Stuart Hall was pretty much at the core of things, and it was euphoric. But by the mid-'90s even radical cultural theory had become somewhat institutionalized.

SO During this time you lot're formulating your views not but on the postcolonial and the global just also on your ain work. Was this when you started dealing with the issue of technology?

OO That came later. Very piddling of information technology had to practice with my cultural experiences. My entry into Net theory was once again a chance thing. When I left England in '95, I knew about email simply hadn't really used it, considering England usually comes to things later than everybody else—except when it'southward about going to fight in the Gulf. (laughter) When I arrived in Chicago and got access to email, I dove right into it and learned how to build my own website, which is yet upward. Surfing at abode in Chicago i morning, I came across an declaration for the Fifth International Conference on Cyberspace. Information technology was already by the deadline for proposals, and I knew aught about internet or cyber theory, but I really wanted to become. When I went through the list of speakers and didn't meet any Africans on it, I thought to myself, "There's my ticket!"(laughter) And so I wrote upward a proposal on the spot and pointed out to the organizers that information technology would be interesting to have an African voice in the debate as well. They saw my point and invited me, and so began my involvement in cyber theory. So I had to read Nicholas Negroponte and the other guys, but of course by the time I got into it my involvement was almost predictable, based on my own experiences and imagining what it was like out in that location in Africa.

And so You lot fabricated the point that the infrastructure wasn't in that location, that one talks most the global community while a large section of the earth is cutting off from that customs for lack of access.

OO It actually had to become part of my larger body of interests, culturally and politically.

SO You left London in the 1990s and came to united states. Was this another one of those chance things?

OO I was pretty decorated as a painter then. I was probably more productive than I have e'er been in my entire career. But London was get-go to shrink on me, and much of information technology had to exercise with segregation within the London art globe, and it wasn't merely segregation forth race lines, information technology was also along grade lines. The class segregation was far more confusing. Information technology was defined in terms of where you studied: Goldsmiths, Primal School at St. Martins, Chelsea or the Slade, and if you didn't written report art in whatever of those places, y'all didn't stand a gamble. I just wasn't part of the scene. So I would have exhibition openings and the audience would be all black, and if I went to some white friend'due south opening, the audience would exist all white. The more I experienced that, the more than it threatened to practise harm to my mind. I plant myself doing more than and more exhibitions in continental Europe. Finally, I decided that it was better to become elsewhere. I got a task offer in South Africa, simply turned it down. It was only a year after apartheid. Then I accepted some other offering at the University of Illinois at Chicago, as well as an invitation to come assistance launch the magazineNka: Journal of Contemporary African Fine art.

SO Was this fulfilling your dream of having your own magazine?

OO Well, long earlier that I had been the production editor of a monthly political newsletter and an art editor for another magazine. So I had experience that could help goNka off the footing. Those were exciting times.

Bridge, 2002, impromptu installation and performance, Loiza, Puerto Rico. Courtesy of M&One thousand Proyectos.

SO How does all this feed back into your own piece of work? What kinds of bug were you dealing with in your paintings?

OO There was a continuation from the work I fabricated prior to leaving Nigeria to the work that I fabricated in England, with 1 exception: in England I returned to canvas and paper, watercolor and acrylic. But the work was still anchored in a number of interests: a socially engaged aesthetic and a continuous exploration of culling aesthetic traditions, not simply African at this betoken but also Australian aboriginal, Native American and so on. And I was interested in questions virtually painting itself. I was exploring all these at the aforementioned time, trying to see how they came together. Just and then I quit painting for viii years. I likewise quit poetry and never wrote over again until final year. I began to make installations. With installations, the form was secondary to the efficacy of the piece in communicating the idea.

So You also started curating effectually this time.

OO Aye. I'd always seen myself as an organizer, but curating was a labor of love. It all began with people budgeted me and saying, "You've written nearly this, how almost helping us put an exhibition or a conference together?" I would say, "Without question." In all the years that I have curated, only once take I approached a space with a proposal. All my other shows have been by invitation; that mode the resource are there, the enthusiasm is there, in that location'southward some level of institutional support, so I can concentrate on making curatorial choices and extrapolating on whatever idea is existence pursued.

SO Do you discover that your being a curator/writer/theorist/artist confuses people?

OO All the time. I tin can't help it, though; that's who I am. When I expect at the possibilities of greater success through concentration in whatsoever one expanse, I accept to balance that for myself with a certain confidence that this is a gift that I have a responsibleness to appreciate. But it can exist difficult, because society makes me question how sensible the path I've chosen is. The truth is, I didn't actually choose a path. I just pursued opportunities that challenged me.

SO Practice you conceive of it all every bit one project, or is it that all these things interest you, so each i is its own projection? Is it totalizing or rhizomatic?

OO That'southward a wonderful mode to put it. What I say to myself in moments of doubt, and there are a lot of those, is, Information technology had better all come together. I have a sense that there's a unifying logic to it. There seem to be a number of interests that run through the projects, no thing the language or medium, and those interests are more social and intellectual and far less reflexive, far less abstract. They are by and large about place, voice, loss, the ambivalence of narrative and language; linguistic communication in terms of form as vehicle, what I oft refer to equally eloquence or efficacious beauty. And of course there'south also the unifying logic of the self.

SO I've been reading the new translations of Walter Benjamin and his stuff on children's-book illustrations and on color. I found a half-folio notation he had written to himself about Mickey Mouse. I realized that he could grab anything, pull it in, look at it, explore it and report on his observation of it. Do you find it similar for yourself?

OO Yeah, absolutely. It's closer to how we feel things: they happen simultaneously, irrespective of where you are. It'south very difficult to differentiate amongst experiences. Of course, some people consciously experience with greater intensity than others. For those who become back and regurgitate such experiences, the higher the level of their conscious appointment and involvement, the less selective they are in what they reflect on.

Then You're basically saying that we're promiscuous.

OO Absolutely. That's a wonderful term. Promiscuity has consequences, of class, because if division of labor, specialization and concentration didn't exist, progress would exist almost impossible. But I recall that's how life ought to be lived.

Brewster Firm, 2002, site-specific installation with gilded mirror, Brewster, New York.

Then What seduces y'all these days? (laughter)

OO There are several things on the horizon at the moment. I'm excited also every bit apprehensive near returning to the classroom; I haven't been at that place on a day-to-day footing for several years. Information technology's an surroundings that I thrive in—that is, if you were to pry off the lilliputian politics of the academy. Too, my nerveless poems will probably be published this twelvemonth, and my volumeThe Culture Game has just been published by the Academy of Minnesota Printing. Right now I'yard recovering the intense pleasure I had making work on a regular basis in the '90s, and I'chiliad exhibiting regularly in major shows and biennials. I'grand as well planning to expand a contempo essay, "God'due south Transistor Radio," on what I've learned in the process regarding the postcolonial predicament.

SO Whataccept yous learned?

OO I've arrived at the conclusion that the impact of colonialism has been misunderstood. Little attending has been paid to the nature of culture as a resilient entity. Fifty-fifty then, I am very interested in the loss of language as office of the postcolonial condition. I published "God'south Transistor Radio" not so long ago, and I'm already beginning to question my ain argument in the essay. (laughter) Presently afterwards I wrote it, it occurred to me that there are significant areas of loss that are actually taken for granted, that are rarely office of the discourse; the loss of language or tongue, for example. Most people dwell on the more visible destruction that was wrought by the colonial come across just fail to grasp the severity of loss, the crisis, in other areas. Perhaps I need to unpack that. I accept only established a literary prize,Ugo Edemede Igbo Anyamele Oguibe or the Anyamele Oguibe Prize for Writing in the Igbo Language, considering my generation is largely illiterate in our linguistic communication, although we are perfectly literate in English and other European languages. In African literature, linguistic communication has been an issue for decades. One argument is that as long as a work is written by an African, it is African literature—even if it is written in English. A less favored school of thought, however, poses the question, What do we lose when we write in everyone else's language but ours? It becomes a matter of survival, a affair of utmost priority, considering, equally Chinua Achebe put it, language is the destiny of a people. People may lose land, or even their liberty, and still come up back and reclaim it. But a people that has lost its language has lost everything. The postcolonial mind is saddled with a colonial malaise: we are not only inept in our own tongues, we are embarrassed to acknowledge what we have lost. I am interested in what Chaucer did for the English in reviving their pride in their own tongue, and Dante for the Italians in spite of Latin, and how Pushkin revived the Russian language when French was the linguistic communication of "civilized" discourse. I'm drawn to invest more in a journey of recovery. I think that's the ballast of my preoccupations.

And so Is your painting, or the painting you plan to do, an attempt to articulate a cultural conflict or perhaps to recuperate a visual experience?

OO A cultural sensibility is closer to it. At this point I am interested in only exploring form and trying to reconnect with a tradition that explores grade and nature. Although I pay a great bargain of attention to grade and beauty as a vehicle, my preoccupation and then far has been largely thematic. Now I want it to be about pure pleasure.

And so But it does have a political date in the real sense of the word: politics as an economy of power.

OO Yes, absolutely. But that's not the sense in which most people understand political art. And that's the point I want to make: the thought of art for pleasure's sake is part of the tradition that I want to return to.

And so Jean-Francois Lyotard, in his essay "On the Sublime," writes about aesthetics every bit a form of resistance. Marcuse also proposes the pleasurable as a form of resistance, considering it ultimately leads to play and nonlinear logics that upper-case letter tin't bargain with.

OO Which is the one point that nearly other Marxists missed completely. I want to keep information technology around, get in part of this more holistic exploration of the Igbo world that I'm gradually returning to.

Ashes, 2002, installation. In this exploration of cataclysm somewhat inspired past the Earth Trade Center tragedy, a city dweller is preparing for work in the morning when an unnamed catastrophe strikes.

SO In this context, permit's go back to the paintings. Given where you're now located, how exercise you imagine the reception of the work that you're thinking about? That is, it will no uncertainty be seen as office of the traditional discourse of abstruse painting.

OO I would have no problem any with its being part of the traditional discourse of abstraction, even in the W. In fact I desire it to be. That and then takes care of that contested history of interconnectedness.

SO You really see it equally a grade of recuperating sure discourses.

OO Yeah. Just I'chiliad especially invested in the thought of trying to make information technology conscious. Not just recuperating it but consciously re-linking it with the bespeak of rupture and trying to constitute some semblance of continuity. More than important, I want to see what there is left to reclaim and how coordinating it is to gimmicky preoccupations.

And then Tin y'all imagine an alternative modernism that doesn't necessary ground itself in Westernization?

OO I've always been reluctant to think of nonwestern cultures and modernism in the same breath.

SO Well, modernism originates with the desire to have the power to create the contemporary, a present, so to speak. At that place'south this notion that y'all could create a disruption in historical continuity and that the ability to create the present was a manifestation of the will. The Americans took the European version of modernism and made it positivist; their inability to bargain with its nihilist aspects led to their making it progressive and linear. Merely the idea of modernizing i'due south civilization originates with people saying, "We can't live in the past, we need to revitalize our civilization. There are aspects of the culture that can be brought frontwards that produce a new present for united states, but nosotros don't necessarily demand to keep it all."

OO Right on. I need say no more! (laughter)I think that'south what the whole project is about. It becomes very complex, because it raises a question of the context of its ain realization. What are the geopolitical requirements for that kind of cultural moment to happen? But that's not something I tin can go into now. (laughter)

Source: https://bombmagazine.org/articles/olu-oguibe/

0 Response to "Olu Oguibes Finding a Place Nigerian Artists in the Contemporary Art World"

Post a Comment